By Friday, Scoresby was reflecting on the season so far, and beginning to feel more optimistic about the days to come. A large opening in the ice had been spotted some way off, and when the Resolution made sail, around 20 ships followed:

Our prospect [sic] hitherto of gaining the Northern water or fishing ground have rarely been favourable. They however now brighten a little from the appearance of a strong blink of much water from NE to SE of us and so high as to judge its distance could not be more than 15 or 20 miles … it is an assurance of the above since two Ships mentioned yesterday as being 15 miles Distant to the NEd of us have disappeared and indeed do not come into sight altho’ we have approached the spot to within 8 or 9 miles …

Jackson notes that “blink” was most often seen as an indication of ice, not water, but it seems likely that sailors of Scoresby’s experience could ‘read’ the blink, and be able to tell the state of the sea in the distance. Indeed, Jackson notes that in Account of the Arctic Regions I, Scoresby mentions his father doing exactly that:

Observing by the blink, a field of ice surrounded by open water, at a great distance northward, [my father] immediately stood towards it, though the wind was south, the weather tempestuous, and the intervening ice apparently closely packed. To the astonishment of the seamen of his own, and the masters of some accompanying ships, he, after some hours arduous manoeuvring, gained the edge of the field. His crew immediately began a successful fishery, while the people belonging to the ships they left, had sufficient employment in providing for their own safety. (p. 384)

The Hull Whaling Fleet of Sir Samuel Standidge, painted in 1788. Hull Museums.

On Wednesday morning, as Scoresby attempted to navigate the ship through the ice, the Resolution was struck by a large piece, and a whale boat stove in. Its skids–a wooden fender designed to protect the boat from impact–and the gangway steps, were torn away. Ice was everywhere, large blocks closing in, and snow falling. Scoresby counted 14 ships nearby, many of them moored to pieces of ice, unable to make way. By 6pm, however, he was able to thread the ship into an opening in which lay the Aimwell, and the Sarah and Elizabeth, followed by another ten ships.

On Thursday 23rd, the ice opened considerably, and with many ships in company the Resolution made progress. All around were whale ships, some 29 in number, some having taken whales, others in pursuit. Among the icebergs: masts, and the cries of men.

During the day it was discovered that the whale Scoresby’s boat had struck on the 19th, but which had escaped under the ice, was indeed the same dead whale picked up by the Augusta. The Augusta was a Hull ship, captained by William Beadling, who, like Scoresby, was enjoying his first command. Realising the line, and the harpoon must have been recovered along with the whale, Scoresby asked that they be returned. Captain Beadling refused “giving some frivolous excuse”. Scoresby then asked that the armourer of the Resolution be allowed to remove the ship’s name from the harpoon, to prevent confusion. Beadling “answered that he would not have the name erased the fortune of fishing had thrown the Harpoon into his Hands & he was determined not only to keep it but to refuse indulging my request which one would have supposed was undeniable. I troubled him no more and accounted for his ridiculous behaviour atributing it to want of sense.”

Ian C. Jackson points out in a footnote to this entry that Scoresby did not assert this principle of ownership in later work, and cites the section on Laws of the Whale Fishery in Account of the Arctic Regions II (pp312-333), in which Scoresby describes the case of the Neptune, one of the boats from which was abandoned secured to a sounding whale, with the purpose of recovering the boat when the dying whale surfaced. Another ship, the Experiment then moved in and captured, the whale, harpoons, and boat, resulting in a dispute that went to court. There Lord Ellenborough found that while the boat should be returned to the captain of the Neptune, the other items, including the harpoon, had become the property of the Experiment.

This dispute over property clearly angered Scoresby, but at the end of his entry for May 23rd he gives us a rare glimpse into the character of one of his crew, Dunbar, the man he sent to talk to Captain Beadling. We learn that Dunbar was known for his sharp wit, and Scoresby says “I almost wished I had given Dunbar liberty to use his oratorial powers in mortifying the fellow since at wit [he is] no contemptible votary.” And Scoresby gives an example of Dunbar’s powers:

The following instance of it related by the Surgeon who heard it fully … [A?] youth on board not remarkable for the beauty of his person or face relating his love affairs &c Dunbar wondered any women should have any liking for so ordinary a looking person as him for he observes … “If I hadn’t known that God Almighty made every body, I’ll be d–nd but I should have taken you for a counterfeit.”

The season so far had been a constant struggle with the ice, and on Wednesday, the crew of the Resolution continued to force the ship to an opening, with around 20 ships nearby in the same situation. Whales were seen, and pursued, by many boats from many ships, and the Augusta of Hull found a dead whale, which Scoresby thought may well have been the one they had killed and lost a few days earlier. The ice was difficult, and dangerous:

Last night Captn Hornby of the Burnie* took Tea with us he said when beset within 1 1/2 or 2 miles of us about 10th May while we lay secured and comfortable in Bay Ice the Bernie was caught between two heavy pieces best in Bay Floes and so pressed that he thinks if it had not been for their activity and exirtion in launching Boats across the Bay Ice near the pieces which pressed them that the Ship must have been stove. The pressure was severe.

*Several variations on this name occur. Jackson also says that while 1811 was the first season for the Bernie, records of the ship appear as early as 1804.

On Tuesday the Resolution, and a large number of the fleet were still trapped.

… set main stay sail Troy sail and Fore sail under which sail with two close reefed Top Sails and F,T,M Stay Sail began to ply to windward most of the Ships in sight under easy sail[.]

Later in the day the fleet followed the Resolution through an opening, but the ice was still close-packed, and Scoresby hints at the lean season, saying that of the 21 ships nearby, onle three had taken whales. even in this tight situation, “A Whale was struck by Vigilant but lost presently afterwards[.] About Mid night the wind had fallen to nearly calm, water freezing[.]”

After losing the whale, the Resolution became trapped in a small opeing in the ice, and though there was open water nearby, it was too dangerous to attempt to reach it:

Reduced the sails to two close reefed Top sails and Fore Stay sail under which we kept our situations laying too and wearing occasionally[.] Several ships in sight some near us[.] One of them appears to be fished (This is known from the custom of suspending the Spacktackle Blocks when a Ship is clean, which are let down on the Capture of a Whale[.]

Scoresby kept the Resolution moving to keep the water clear.

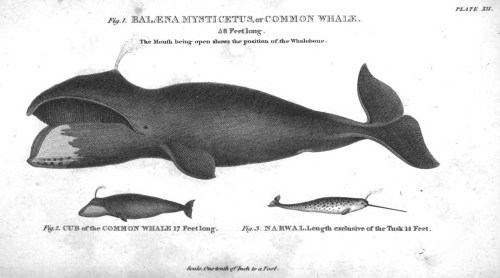

In the morning the Resolution followed several other ships out of the ice, and into more open water, yet still the amount of ice was troubling. Of more immediate importance, however, was the appearance of whales. Boats were lowered, and a “Mysticetus“, or Common Whale, was struck. Although the whale was in open water, it ran for the cover of a patch of ice two miles across. Scoresby sent some of his officers across the ice, and they found the whale, which had broken through to breathe, and killed it with lances. The whale sank, and it was hoped they could pull the body out from under the ice:

She had run out 7 1/2 lines[.] Took an end to the Ship and began to heave on the Capstern[.] After getting in about a line we had a very heavy strain about as much as the line was calculated to bear with safety[.] The line lay very horizontal from which we supposed the whale had not sunk, but lay under some rough Ice or behind some hummock under the surface. … 3 1/2 lines were lost and 3 of those saved were nearly spoiled by being over strained. The Mate with 3 men went to the place where she died. Here they sounded with Boathook &c on the further edges of all the heavy pieces of Ice near within 200 yards al[so] through numerous places of the then flat of Ice under which she went. They found her not.

The whale principally hunted by William Scoresby, and the Greenland whale fleet, in the early nineteenth century, was Balaena Mysticetus: the Bowhead Whale, then also known as the Greenland Right Whale, or the Common Whale. This whale is native to the Arctic, and spends most of its life near the edges of the ice, migrating North and South as the seasons, and the limits of the ice, dictate. In 1811, stocks of Bowheads were declining, but still more than large enough to make whaling profitable in the Greenland Sea. A decade later, they were much more difficult to find, and whalers turned their attention to the Davis Strait. Commercial whaling continued, of course, until the early 1980s, by which time Bowhead whales were an endangered species, facing extinction. Populations have since grown, but they remain at risk. Around 60 Bowhead whales are still killed each year by indigenous human populations in Alaska.

Here is part of Scoresby’s description of Balaena Mysticetus, from his Account of the Arctic Regions, vol 1 (1820), (pp. 449-477:

This valuable and interesting animal, geneally called The Whale by way of eminence, is the object of our most important commerce to the Polar Seas,–is productive of more oil than any other of the Cetacea, and being less active, slower in its motion, and more timid than any other of the kind, of similar or nearly similar magnitude, is more easily captured.

…

Immediately beneath the skin lies the blubber, or fat, encompassing the whole body of the animal, together with the finsa and tail. Its colour is yellowish-white, or yellow or red. In the very young animal it is always yellowish-white. In some old animals , it resembles the colour of the substance of the salmon. It swims in water. Its thickness all round the body, is 8 or 10 to 20 inches, varying on different parts as well as in different individuals. The lips are composed almost entirely of blubber, and yield from one to two tons of pure oil each. … The blubber and the whalebone are the parts of the whale to which the attention of the fisher is directed. The flesh and boness, excepting the jaw-bones occasionally, are rejected. The blubber in its fresh state is without any unpleasant smell; and it is not until after the termination of the voyage, whe the cargo is unstowed, that a Greenland ship becomes disagreeable.

…

The bones of the fins are analogous, both in proportion and number, to those of the human hand.

The Aimwell was first to break out of the ice, with the Resolution close behind, and while the ice did not disappear, Scoresby wrote with relief that “The Ice seems now to be inclined to open in a general way.” They made their way northward through lanes in the ice as it broke up into large sheets that drifted one way and then another. At the end of Wednesday the 15th, Scoresby was pleased with the strenghth of the wind, but predicted that it wouldn’t last, concluding “from the rising of the Barometer it will soon fail us”.

By Thursday, they were in company with the Aimwell, and the Sarah and Elizabeth, within sight of seven other ships under sail, besides others still beset. As Scoresby had predicted, the wind fell almost to nothing, and the water froze again. He mustered the crew to tow the ship, an activity which continued into Friday with four boats. They were in constant company with other ships, 14 being spotted within a few miles and several others within sight. After a day of towing the ship was moored to the ice at around 1AM on Saturday morning.

However, the ice was in constant motion, and Scoresby was anxious about being beset again. He estimated they were within 500 yards of the western boundary of the ice, and set to towing again soon afterwards:

[B]eing unable to ply further upon account of the Bay Ice sent a boat up with 2 whale lines leaving one end on board the Ship and making the other fast to the weather Ice then taking in the Sails prepared to heave the Ship up but lo! the line became suddenly so stretched so as to be likely to break. We fastened the end and the Ship was turned round and pulled out to Windward of the Bay Ice without heaving in the least upon the line a Distance of 200 or 300 yards. Coming then into clear water hove the Ship up to the Ice.

Scoresby noted, as the ice took hold of them, temporarily, again, that on that day they had seen “40 sail of Ships … the greatest part of the British in Greenland”.

A strong gale blew up on Tuesday, accompanied by snow showers and a heavy frost, the temperature dropping to 11 degrees (around -12 Celcius). The Resolution was secured with towlines, to prevent “falling foul” of the Aimwell, which was just half a ship’s length astern. Then, in the evening, the ice began to break up:

In the morning [of the 15th] this opening had so increased as to be of considerable size. supposing it might lead to the NE which we could not ascertain from the constant snow about noon prepared to sail.

On Monday, the “frost diminished” and lanes of water appeared, bringing some hope of escape. For a while the temperature rose as high as 31 degrees (just below freezing), but by the mid-afternoon had fallen again to 18 degrees (-8 Celcius). Several ships, including the Resolution, attempted without success to bore their way out of the ice. Scoresby lists nine other ships close by, inclusing the Aimwell, and the James of Liverpool:

A swell is now our Chief hope although dangerous when heavy and amongst cose Ice yet is little chance of getting to the Nd without its aid to break up the Bay and thereby disentangle and set the heavy Ice at liberty.